It’s the Monday morning after Thanksgiving break at an Anne Arundel County Public (AACPS) high school. The bell for the start of first period just rang and the School Psychologist is logging notes from her morning’s completed counseling session. The student, one of the 20 that she sees on a regular basis during her three days a week at this school, is struggling to pass most of her classes. They discussed some of the anxiety problems the student was having in class and created a set of goals to tackle this week. Next is a parent phone call to follow up on an incident last week where a teacher found a letter showing suicidal tendencies. The School Psychologist gets some more information about follow-up actions over break and offers resources to help the family provide access to therapy. When the call is over, the School Psychologist prepares for an Individualized Educational Program (IEP) meeting where she, along with a multi-disciplinary school based team, will present the results of recent IEP testing with the mother.

This is the world of the School Psychologist

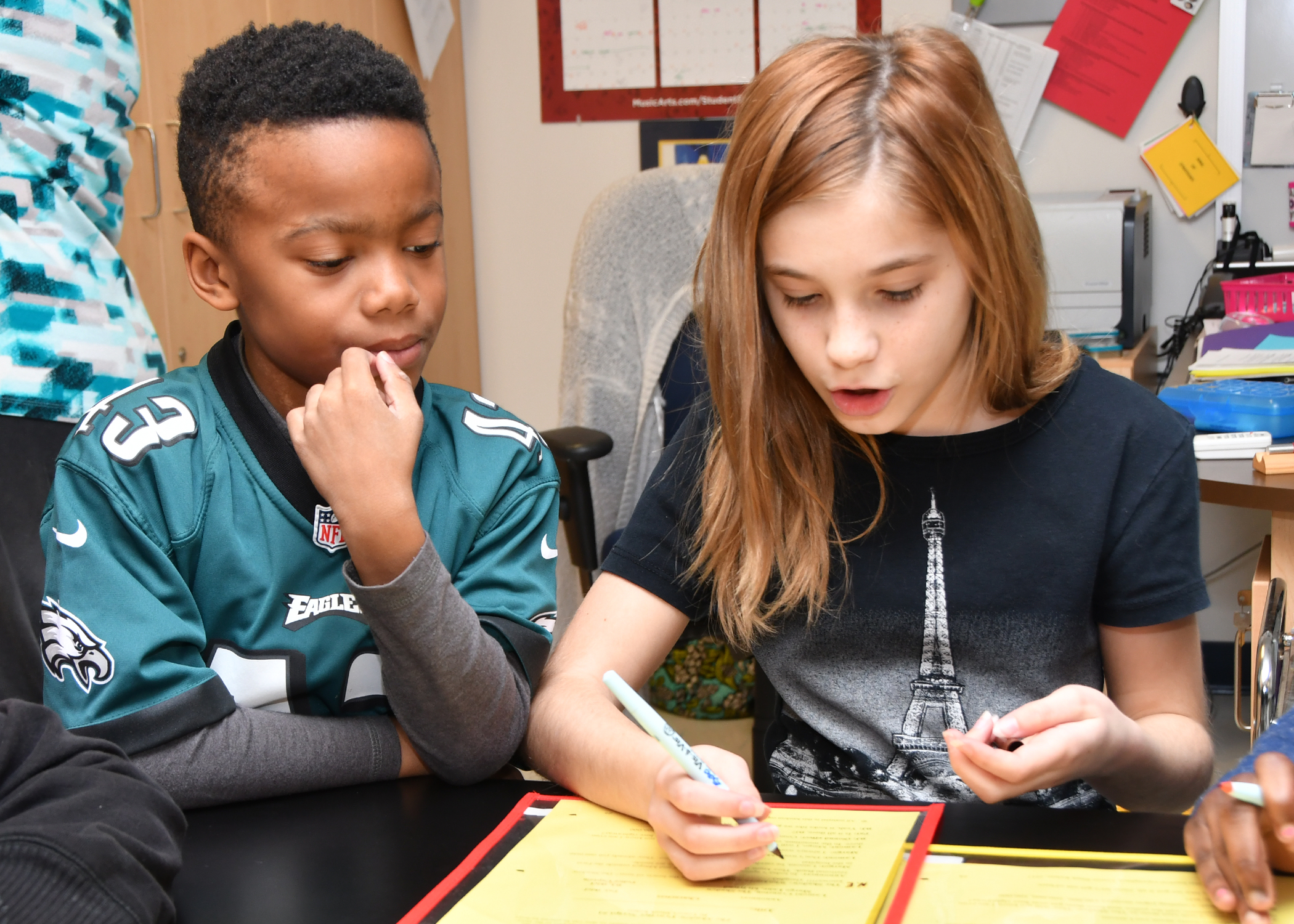

A distinct profession under the umbrella of Student Services, School Psychologists are specially trained mediators and problem solvers who help assess and address students’ emotional and learning needs. Across the county, 64 School Psychologists serve as consultants, crisis interventionists, and direct service providers for students, families, and staff. For the many who are unfamiliar with this role, the idea of a School Psychologist often evokes the one-dimensional image of a therapist sitting one-on-one with students to help evaluate and address individual learning or behavioral needs. In reality, however, these are dynamic members of the school-based team that bring unique education and training to many constantly varying roles.

As an integrated part of the school-based team, School Psychologists are often called for their unique training and understanding of psychological issues and knowledge of special education laws. Here is where their unique training is essential. All AACPS School Psychologists have graduated from a National Association of School Psychologists (NASP)-approved program to prepare them with training and education in curriculum, differentiated instructional strategies, and mental health services. This background equips these professionals with knowledge, resources, and experience to look holistically at each student and help parents, teachers, and staff meet a child’s individual needs.

Servicing the needs of the many as well as with the needs of the few

On Thursday, our School Psychologist is wrapping up her morning at the elementary school where she spends the other two days of her week. By 12:30, she has prepared for and led three counseling sessions, completed part of an ongoing functional behavior assessment, logged her interactions in the AACPS Case Management system database shared with School Counselors, School Social Workers and Pupil Personnel workers, and worked on a mandated IEP report. All of this between the hallway consultations with teachers concerned about individual students, conversations with parents about their child’s progress, and phone calls with other schools to share the history of a transfer student. This variation is typical for School Psychologists across the county who, by the demands of the position, must be adept multitaskers able to not only juggle multiple responsibilities, but still focus on the individual needs of each student that she or he sees, all within the confines of the school day.

Because School Psychologists are one of the few professionals in Student Services able to perform mandated IEP services (along with School Social Workers), this capacity is a daily part of the job. Whether organizing and conducting testing to gauge a child’s cognitive skills and emotional functioning (which takes between 2 and 10 hours, depending on what’s needed for the student), preparing the IEP report (another 2-10 hours) to present to the parent and school-based team, or meeting mandated counseling hours with each student, IEPs are a daily part of the job and, for many, one of the most prominent. If time allows, School Psychologists also help organize individual and group counseling sessions for non IEP students as well, meeting weekly or biweekly to help students develop empathy, manage social anxiety, and find a purpose in life. On an individual basis, the School Psychologist is there to advocate for the voice of the student. Every day, their responsibility is to ensure that each student has access to a free and appropriate education.

But whenever possible, School Psychologists also try to look at the broad needs of general education students and the school as a whole. With resources and knowledge to service everyone, School Psychologists help organize engagement and prevention programs such as anti-bullying initiatives, school beautification days, and resiliency workshops. These opportunities give all students strategies to handle both emotional and academic situations to prevent problems before they escalate or even arise. Focusing on prevention can lead to decreased anxiety and depression, increased social skills, and increased academic achievement. In addition, School Psychologists offer crisis interventions for students who may be in danger of self-harm, or harm to others or for events such as 9/11 and the Sandy Hook shooting and regularly serve as Equity Liaisons, Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS) coaches, Collaborative Decision Making Coaches, and on School Improvement Teams. Through these services, the reach of the school psychologist expands to the entire school.

The challenge is to provide these services under tightly stretched resources. With 64 people to service 120 schools and special centers, one School Psychologist may serve up to four different sites. While almost every high school has a full time School Psychologist on staff five-days a week, 83% of elementary schools only have access to an on-site School Psychologist two days or less each week. NASP recommends having a ratio of one School Psychologist for at least every 700 students (or 1 to every 500 students if the school has special programs); in AACPS, this ratio is about 1 to 1,260.

Finding strength in collaboration

To ensure that they can offer as much support as possible with such limited numbers, School Psychologists depend on the collective strength of their collaborative teams. At every school, they serve on a team of multi-disciplinary players who come together to identify individuals who need intervention support. But across the county, they are also part of AACPS’ network of educators dedicated to providing high quality services to ensure that all students have access to the best education possible.

Friday morning, our School Psychologist arrives at Carver for her Cultural Competency Workgroup. Shira Levy, School Psychologist and chair of this 30-person committee, opens the meeting with an update on the “Voices of Diversity Project” organized by their workgroup. This professional development video series presents current and former AACPS students sharing personal stories about their diverse experiences with military transience, sexual orientation, English Language Acquisition, and Race/Ethnicity. The completed project, designed to generate discussions and facilitate positive change to create stronger school communities, will be presented to Equity Liaisons in February who will then train schools across the county. Next on the agenda is a review of data from the completed Grit ELL Parent Training Program (a six-session series developed for English Language Learner parents to help their students develop passion and persistence towards long-term goals) before moving onto the day’s professional development discussion: School Psychologist Juan Villalta’s presentation on having courageous conversations about race.

To offset limited resources, these collaborative sessions are the norm. One of the 20 committees/Professional Learning Communities (PLC) within the Office of School Psychological Services, each group brings School Psychologists, Interns, and School Social Workers together to discuss and address the diverse needs of AACPS students. From Instructional Technology to suicide interventions to strategies for dealing with Autism, these collaborative working groups bring people together from across the county and leverage the collective resources of their team. And these groups are just one of the many ways in which this highly collaborative team pools their resources to help AACPS. Whether calling to discuss the history of a transfer student or requesting help from one of the 25 School Psychologists trained to administer the ADOS Autism observation scale, School Psychologists are in frequent contact with one another to seek and share resources and expertise.

Back at high school, our School Psychologist prepares for her next meeting: a student working on controlling his anger. She talks with the child’s teacher and reviewed notes from the school counselor who met with the student at the end of last week. She makes notes about the strategies she will share to help the student continue developing appropriate outlets for his emotions. This session, like those that come before and after it, presents its own challenges, and demands dedicated time to identify creative solutions.

Yet what is so much more important is that with every case comes a new student—a child with unique needs, talents, and potential who will become tomorrow’s leader, tax payer, and innovator. Every student has the potential for greatness as long as they are given the opportunity and support, both emotionally and academically, to succeed. Equipped with the tools and training to understand the line between mental health and learning, School Psychologists are here to help each child achieve that greatness.